Introduction Link to heading

This is the 2nd part of my series about health checks in .NET web applications. If you haven’t already, I’d recommend reading the first article which provides a good foundation to build upon and provide context in this post.

It can be found here: Optimizing .NET Health Checks

You can find my github repo containing all code here: magicmatteo/healthcheckseries

Something I’ve come across from time to time that makes me uneasy is health checks that take a significant amount of time. I’m talking about anything from 200ms to multiple seconds.. We must assume that our health check endpoint is going to be spammed quite often. In Kubernetes, your readiness and liveness probes could be running every 5-10 seconds. The more often these probes fire, the more responsive your eviction and load balancing policies can be. Add in some synthetics calling from multiple regions and you could end up with checks that run every other second or even invoked multiple times at once. So making them lightweight is imperative.

Potential culprits Link to heading

There are a number of reasons you could have a slow, or compute intensive health check. Lets explore some example culprits below.

- Slow downstream APIs - The downstream APIs you are checking may be slow themselves for various reasons.

- Database integrity verification - You may be running queries inside your database which could take a long time, depending on the size of the dataset.

- Authentication flows - You might be performing an OAuth flow during your check which contains multiple REST calls

- Cloud storage verification - You could be verifying that you can read & write to SharePoint or Blob storage, which could have slow IO.

- File integrity checking - You may need to hash multiple files to verify their integrity. This is computationally expensive and could take significant time..

Generally speaking - It’s likely going to be due to computationally intensive tasks or slow I/O operations..

Handling slow or expensive checks Link to heading

Now that we know we need to keep our health endpoint lightweight, lets explore how we can tackle it.

The lightest our health endpoint can be, is to simply return a cached health report. To achieve this - we will run a background service, responsible for running the expensive health check on a cadence we are comfortable with. This background service will then cache the result of its health check, which our main health endpoint can retrieve with minimal overhead. It not only reduces the response time of our health endpoint, it also means that you only ever have one instance of the actual health check running.

Lets go with the example of synthetics. Lets say you have a synthetic set up with your observability platform. These can be configured to hit your service - and potentially your health endpoint - from multiple PoPs (points of presence) around the world at once. Depending on the number of replicas you are running, this could mean your health endpoint is called multiple times at once. Depending on the nature of your health checks, this could be a dramatic waste of IO, threads and resources. By implementing this pattern, you will never be running your health check more than you specify. You gain control of how and when it is run. The new health endpoint will be simply returning the cached health info, which is essentially free, so they can hit it as frequently as they want!

Code time! Link to heading

First off, let’s create a new class for our background service. .NET provides the IHostedService interface, which allows us to manage the lifecycle and execution of our health check within dependency injection (DI).. We’ll call it ExpensiveHealthMonitor.cs.

// ExpensiveHealthMonitor.cs

using Microsoft.Extensions.Diagnostics.HealthChecks;

using System.Diagnostics;

namespace HealthCheck;

public class ExpensiveHealthMonitor(IHttpClientFactory httpClientFactory) : IHealthCheck, IHostedService, IDisposable

{

private Timer _timer;

private long _checkMs;

public bool Healthy { get; private set; } = true;

public Task StartAsync(CancellationToken cancellationToken)

{

_timer = new Timer(CheckDependencies, null, TimeSpan.Zero, TimeSpan.FromSeconds(30));

return Task.CompletedTask;

}

public Task StopAsync(CancellationToken cancellationToken)

{

_timer?.Change(Timeout.Infinite, 0);

return Task.CompletedTask;

}

public void Dispose()

{

_timer?.Dispose();

}

public Task<HealthCheckResult> CheckHealthAsync(HealthCheckContext context, CancellationToken cancellationToken = new())

{

Console.WriteLine($"{DateTime.Now.ToLongTimeString()} - Health Endpoint called!");

return Task.FromResult(Healthy

? HealthCheckResult.Healthy($"ExpensiveDependency is Healthy - last check took {_checkMs}ms.")

: HealthCheckResult.Unhealthy("ExpensiveDependency is Unhealthy"));

}

private async void CheckDependencies(object state)

{

var watch = Stopwatch.StartNew();

// Heavy checks go here (async calls, etc.)

// We could have as many as we want here to ultimately determine health

Healthy = await ProbeSlowPokeApi();

watch.Stop();

_checkMs = watch.ElapsedMilliseconds;

Console.WriteLine($"{DateTime.Now.ToLongTimeString()} - Ran PokeApiHealthCheck in the background. " +

$"Took {_checkMs} ms.");

}

private async Task<bool> ProbeSlowPokeApi()

{

var httpClient = httpClientFactory.CreateClient();

// Simulate some delay in the request

await Task.Delay(700);

var response = await httpClient.GetAsync($"https://pokeapi.co/api/v2/pokemon/slowpoke");

return response.IsSuccessStatusCode;

}

}

Breaking it down Link to heading

There is a little bit in here to unpack - so let’s take it bit by bit. I will list each section of code, describing each section underneath.

public class ExpensiveHealthMonitor(IHttpClientFactory httpClientFactory) : IHealthCheck, IHostedService, IDisposable

{

private Timer _timer;

private long _checkMs;

public bool Healthy { get; private set; } = true;

public Task StartAsync(CancellationToken cancellationToken)

{

_timer = new Timer(CheckDependencies, null, TimeSpan.Zero, TimeSpan.FromSeconds(30));

return Task.CompletedTask;

}

public Task StopAsync(CancellationToken cancellationToken)

{

_timer?.Change(Timeout.Infinite, 0);

return Task.CompletedTask;

}

public void Dispose()

{

_timer?.Dispose();

}

We are using a primary constructor here because the injection is very simple, just an HttpClientFactory. You can see that we are implementing IHostedService, IDisposable & IHealthCheck. I’ve decided to also keep the IHealthCheck logic inside this class too. This allows sharing some common data - such as the time it took to execute the last check (_checkMs).

The StartAsync() method is the entry point for our background service. We define a Timer in here, which allows us to specify the method to execute and its schedule.. For this demo, we’ll configure it to run every 30 seconds. You should adjust this according to your requirements. We also have the StopAsync() and Dispose() methods, which stop the Timer from looping and dispose of it.

Ultimately, this is the scheduler that wraps the logic for our expensive health check, giving us the control to run it at our own pace.

private async void CheckDependencies(object state)

{

var watch = Stopwatch.StartNew();

// Heavy checks go here (async calls, etc.)

// We could have as many as we want here to ultimately determine health Healthy = await ProbeSlowPokeApi();

Healthy = await ProbeSlowPokeApi();

watch.Stop();

_checkMs = watch.ElapsedMilliseconds;

Console.WriteLine($"{DateTime.Now.ToLongTimeString()} - Ran PokeApiHealthCheck in the background. " +

$"Took {_checkMs} ms.");

}

private async Task<bool> ProbeSlowPokeApi()

{

var httpClient = httpClientFactory.CreateClient();

// Simulate some delay in the request

await Task.Delay(700);

var response = await httpClient.GetAsync($"https://pokeapi.co/api/v2/pokemon/slowpoke");

return response.IsSuccessStatusCode;

}

Next we define our health check logic inside the CheckDependencies method. This is where we should be making all of our async calls. In cases where we have multiple checks, they should all be run in parallel. I’ve placed a watch around the execution for demo purposes, and to report on within our health endpoint. To simulate a slower API call, I’ve added a 700ms sleep to ProbeSlowpokeApi(). You can see that we are storing the result of the health check in the Healthy property for later retrieval by the health endpoint. This is the caching magic that makes it blazingly fast!

public Task<HealthCheckResult> CheckHealthAsync(HealthCheckContext context, CancellationToken cancellationToken = new())

{

Console.WriteLine($"{DateTime.Now.ToLongTimeString()} - Health Endpoint called!");

return Task.FromResult(Healthy

? HealthCheckResult.Healthy($"ExpensiveDependency is Healthy - last check took {_checkMs}ms.")

: HealthCheckResult.Unhealthy("ExpensiveDependency is Unhealthy"));

}

Of course we cant forget our CheckHealthAsync method, which is called by the health check middleware to report the status back to the user. This doesn’t have to exist in this class but I have included it in here today for simplicity. You could have this in a separate class purely responsible for returning the health check result, in which case you’d need to inject our singleton ExpensiveHealthMonitor service into it, and fetch the public Healthy property. Having it in here also allows us to cheekily add the execution time into the description displayed by the endpoint.

Registering the service Link to heading

We’ll need to register the service as a singleton, so it maintains a single instance of the cached health state. Registering it as a singleton, instead of just a HostedService, also allows it to be injected into other services correctly should you need that, so I’d recommend the below method. Then we just register the check as we would any other.

builder.Services.AddSingleton<ExpensiveHealthMonitor>();

builder.Services.AddHostedService(p => p.GetRequiredService<ExpensiveHealthMonitor>());

builder.Services.AddHealthChecks()

.AddCheck<CustomHealthCheck>("PokeApi")

.AddCheck<ExpensiveHealthMonitor>("ExpensiveHealthCheck");

Observing the results Link to heading

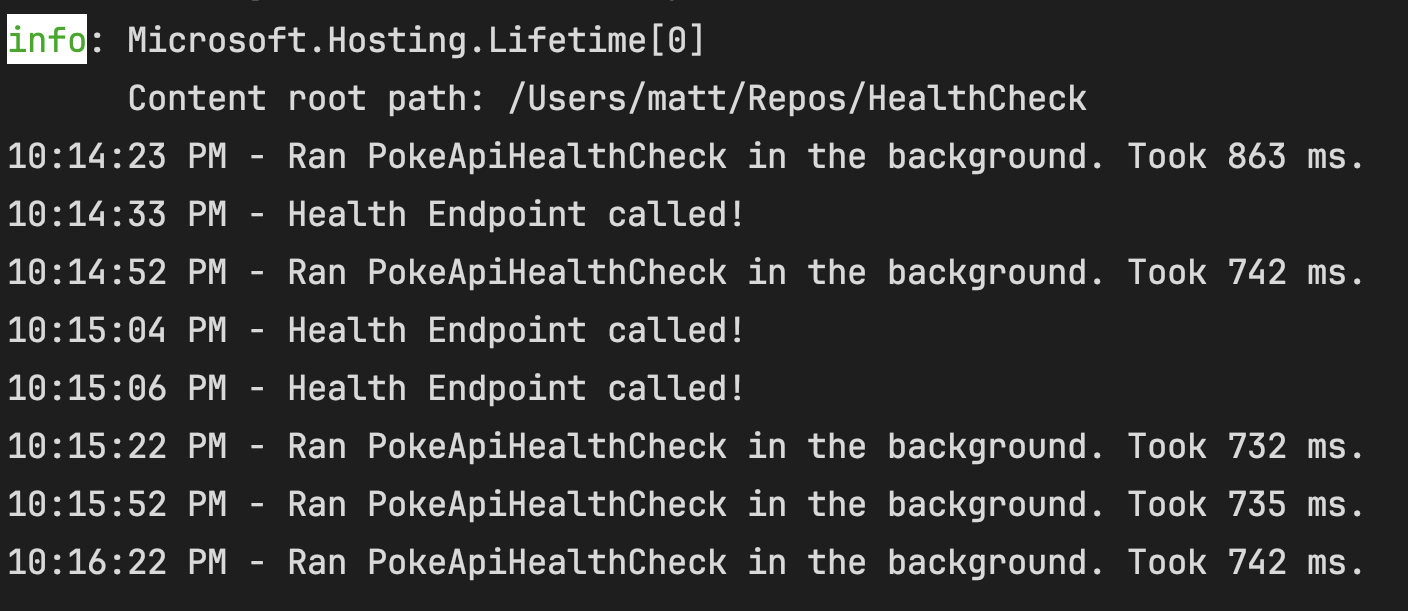

You can see by the console logs that no matter how much we call our health endpoint, the background health check will only ever run once every 30 seconds, with an execution time of roughly 700ms.

And our health endpoint output. An impressive 20ms execution time all up, but this is mostly from the raw http call we are still making as part of our other health check. You can see that retrieving the health status in question only took 99 microseconds. Blazingly fast!

{

"status": "Healthy",

"totalDuration": "00:00:00.0208810",

"entries": {

"PokeApi": {

"data": {

},

"description": "PokeAPI is healthy",

"duration": "00:00:00.0207156",

"status": "Healthy",

"tags": []

},

"ExpensiveHealthCheck": {

"data": {

},

"description": "ExpensiveDependency is Healthy - last check took 780ms.",

"duration": "00:00:00.0000997",

"status": "Healthy",

"tags": []

}

}

}

Conclusion Link to heading

If you’ve made it this far - thank you for reading the second part of my HealthChecks series. We covered a nice little pattern for running our health checks asynchronously, allowing our main health endpoint to return data promptly, with no overhead. I hope it will be of use to you one day. Stay tuned for my next article, where I’ll deep dive into defining pragmatic liveness and readiness probes for Kubernetes using the methods we’ve covered.

Until next time :)